Why Is This Famous?

Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks”

“Ed refuses to take any interest in the very likely prospect of being bombed”

In our series Why Is This Famous?, we aim to answer the unanswerable: How does a work actually enter the public consciousness? (See all installments.)

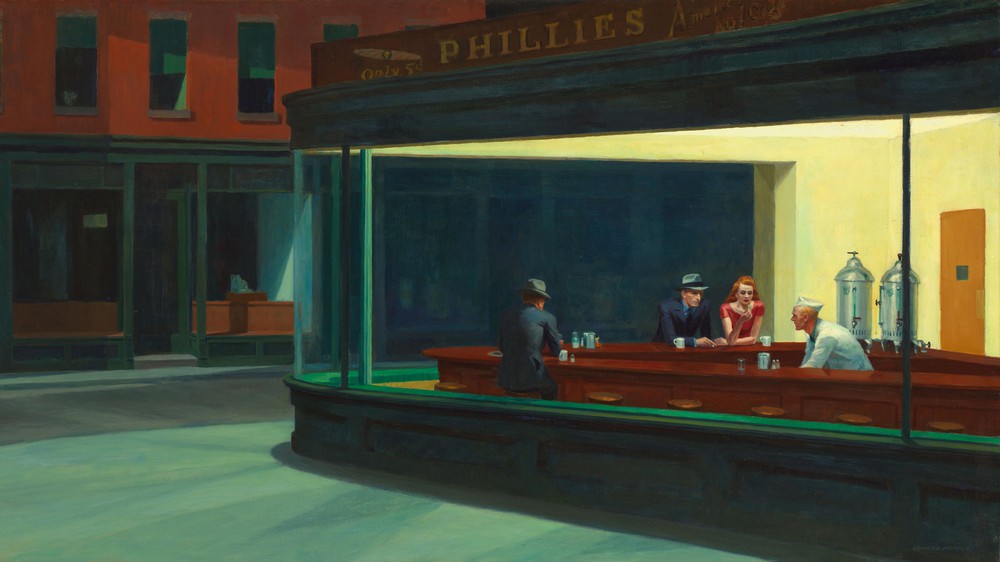

Like many of the other works we’ve covered on “Why Is This Famous?”, Edward Hopper’s 1942 painting Nighthawks has been widely parodied; notably in The Simpsons, That 70s’ Show, and in New Yorker cartoons. While Hopper sold the painting to the Art Institute of Chicago (where it remains today) for only $3,000 ($45,875 in 2018) a few months after its completion, it is the painting that solidified his fame and lifted the value of his other works; for example, the much less famous East Wind Over Weekwaken (1934) sold for $40.5 million in 2013.

The painting is widely understood to capture the isolation and loneliness of Americans during World War II, while maintaining the nostalgia and familiarity we seek in Americana. But of course many of Hopper’s masterpieces evoke solitude, so why has Nighthawks especially endured in the popular imagination?

Windows and doors

Edward Hopper was born near the Hudson River, in Nyack, New York in 1882. He was always a loner. His parents noticed his artistic talents when he was just 10 years old and, soon after, enrolled him in art school. He studied under the Ashcan School co-founder Robert Henri, who instilled in Hopper that artworks should express life and emotion. Like a good art student, Hopper ran with Henri’s advice. Like a great artist, he did so without directly copying his teacher.

Hopper came up in the art world just as the World Wars were preparing the average American to feel like, well, they were in a Hopper painting: quietly isolated, lonely, numb. His work rendered these emotions routine, comfortable, and familiar, and therefore prevented them from being devastating or destructive. Likewise, in Nighthawks, Hopper makes the viewer feel lonely in a way that feels sublime but true. We are placed outside of the diner that holds the only sign of warmth or activity in the entire painting, but there is no door that would allow us to enter. We are allowed to peer into the scene by the large, clear window—a device Hopper often used to simultaneously keep his subjects at a distance while granting us access into their world (see Night Windows (1928), and Office in a Small City (1953)). Unlike his contemporary Norman Rockwell, who expertly made windows look like windows (see Window Washer (1960)), Hopper’s windows seem to act as doors.

The introverted Hopper married Josephine “Jo” Hopper in 1924, a gregarious painter who would find herself constantly plagued by her husband’s affinity for solitude. Many great artists are notorious for denying viewers insight into the meaning of their work, and Hopper is no exception. Jo, however, kept detailed diaries of her husband’s life and work, which function like Hopper’s windows do for his subject—they give us insights into the artist that are otherwise barricaded by his structures and paints.

The world, tomorrow

Jo’s diaries tell us that Hopper completed the painting in late January 1942, just weeks after the December 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. Living in New York, the Hoppers, like most Americans, did not know if they were safe or if they should expect their city to soon go up in flames; Jo writes, “Ed refuses to take any interest in the very likely prospect of being bombed.”

The windows and storefronts on the street are just as clear as that of the diner, but instead emphasize the emptiness and lack of life behind them. The diner itself doesn’t even have any merchandise, only a cash register that we can guess hasn’t seen much use lately. We can easily imagine what this street corner once looked like—bustling with apartments, stores, and a diner either before the war, or as recently as the during the day. We know it may look that way again, whether that’s after the war or tomorrow afternoon. This type of anticipation and not-knowing defined the American attitude in the winter of 1942. It was the height of the violence of the second World War, and no one could predict what the world would look like tomorrow. Nighthawks shows us that American life and culture is not yet dead, that it endures even through the dark, empty night.

- Click to Add to playlist

- Click to Favorite

What we do know about Nighthawks is that it is distinctly and familiarly American. Hopper’s diner is smooth and simple and generalized enough for viewers to insert their own lives into the scene. But he has painstakingly detailed the napkin holders, salt shakers, coffee mugs, coffee urns, swivel chairs, and server’s uniform to place us in a quintessential American diner. There is no clear narrative, and it is unclear who is and isn’t conversing, or what the relationships between the characters are, but we know that we’ve been to that diner before. We can even believe that we’ve seen those people before, even though they could be anyone.

One of the most enduring questions in Nighthawks is whether the diner, which seems so familiar and unattainable, is a real place. (Sound familiar?) Art fans have searched for the exact diner for decades, basing their quest off of one of Hopper’s predictably vague quotes, that it’s “a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet.” There are blogs and clubs dedicated to uncovering the mysterious diner, but in 2010, the New York Times reported that they are certain that the diner never existed. This enduring quest to locate the familiar yet mysterious site underscores that viewers are still plagued by the simultaneous knowing and not-knowing. This is at the core of Hopper’s appeal: a loneliness that feels general but specific, familiar but uncomfortably distant. He was the master of creating a mystery that could never be solved, one which we feel compelled to continue investigating.