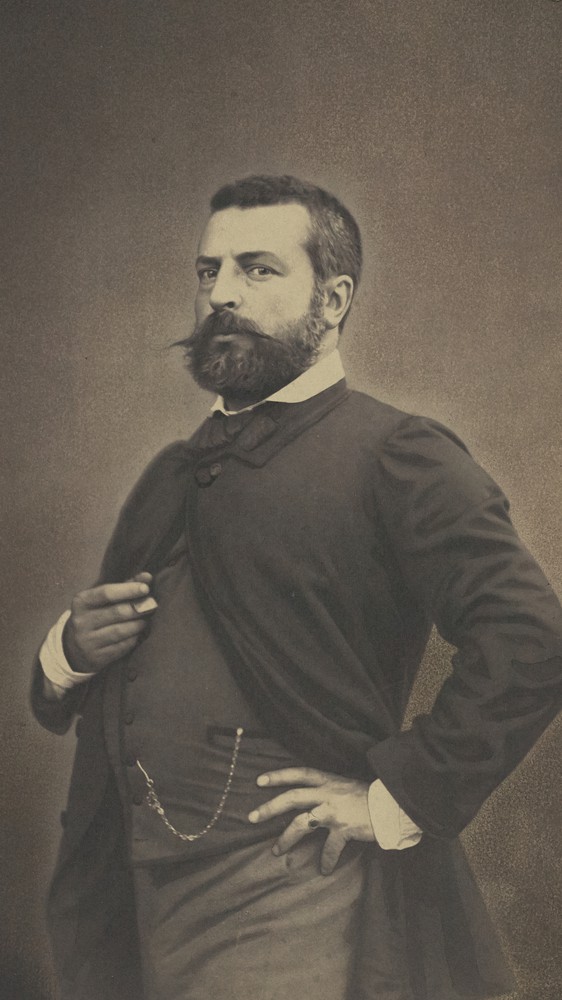

Was Nadar His Time’s “Most Interesting Man in the World”?

The unlikely hero of aerial photography

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, also known as Nadar (more on that later), wasn’t a Renaissance man, per se. But in his 90 years (1820–1910), the French photographer racked up ten lifetime’s worth of achievement. He did so many odd, amazing things that together the list seems apocryphal, the creation of a fanciful biographer: He photographed an immense range of celebrities (including Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, Eugène Delacroix, Franz Liszt, Claude Debussy, and the King of Persia), inspired Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon (and a character in From the Earth to the Moon), was the first to use artificial lighting in photography, invented crowd-control barriers (still known today as “Nadar barriers”), organized the world’s first airmail service, hosted the Impressionists’ first exhibit, and predicted that airplanes would take the place of hot-air balloons. And this isn’t to mention his most unbelievable accomplishment: taking the world’s first aerial photograph.

Sources don’t agree even on Nadar’s birthplace—it may be Paris or Lyon. His achievements seem to begin as soon as he departed from what would be a comfortable life. After dropping out of medical school, he started writing and drawing for a few newspapers and befriended some of the most brilliant men of his time, including Baudelaire and Théodore de Banville. It was this group that would give him his nickname—which is, again, disputed. It either came from his habit of adding “dar” to the end of words (and so his friends called him Tournadar, and then Nadar), or from the phrase “tourne à dar,” or “the one who twists the dart.”

At the age of 34, Nadar opened up his photography studio. Against the trends of the time, which favored ornate, contrived decoration, Nadar favored simplicity. It was a hit. He would go on to photograph some of the most memorable personalities of his generation, from academics to actresses (including Sarah Bernhardt, who was also the subject of the Alphonse Mucha poster that made him famous). His wilder affinities, such as taking images underground, forced him to pioneer the use of artificial lighting in photography. But this wouldn’t be his last contribution to the field. In those days, photography was a nascent medium and still in its scientific phases; Nadar’s studio would also serve as a laboratory.

Only a few years into his practice, he decided he needed to take photography to new heights, literally. This would be hard enough, given the immobility of most cameras. It was made nearly impossible by the fact that the technology of the day required the use of a wet plate collodion process, a technique involving intricate chemistry that was knocked off balance by the unwieldy circumstances of a hot-air balloon. And yet, in 1858, he did it. The image hasn’t survived the years, though Honoré Daumier immortalized the moment with a lithograph. (The honor of taking the first aerial photograph we still have today goes to James Wallace Black, for his shot, Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It, taken two years later.)

Nadar’s taste for the sky was just beginning. He knew that if he wanted to take more photographs in the air, he’d need a larger, more stable platform to do it from. And so, five years after his first aerial photograph, he commissioned the French aeronaut Eugène Godard to create a gigantic balloon, what was known as Le Géant. In those days, this was something to behold, and the event attracted an unwieldy crowd. In fact, the sheer number of spectators led Nadar himself to invent the crowd-control barrier.

Like a modern telling of Icarus, the device was doomed to fail from the beginning—it crashed badly on its second flight and made only five flights in all. But it inspired many to think about what else was possible (it helped inspire Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon). Nadar’s mistrials also gave him a vision of today; he predicted that sustainable flight would be unachievable unless the aircraft pushed air downward (the technique modern aircrafts rely on).

If Nadar was indulging his own whimsy with the commission of Le Géant, his aerial imagination would be put to more practical use a few years later. 1870 brought the Franco-Prussian War and the five-month Siege of Paris, a time when Parisians had no way of communicating with the rest of France. Mail would literally have to be lifted out of the city and brought to its destination by air—and that’s exactly what Nadar plotted to do. By the end of the war, 66 successful trips made by balloon had been made (only five were captured by the Prussians; three went missing), scattering a total of 2.5 million letters across the country. Though the service charged its users, it wasn’t ultimately a profitable affair; some sources note that the startup nearly bankrupted Nadar.

He eventually climbed his way back, through his photography of course. For the remaining decades of his life, his studio would provide him both financial and creative sustenance, and a part of history. In 1874, it was the home of the Impressionist’s grand opening exhibition, a show that featured 30 artists, including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Cézanne, and Edgar Degas. Even after Nadar’s death, the studio got a second life in the hands of his son, Paul.

The legacy Nadar left was scattered but simple: think big; think small. While he quite literally reached for the stars, his artistic endeavors left no room for frills. While he paid immense sums to forge new technologies, it was for the creation of art. While his adventures fomented public hysteria, his ultimate contributions were lasting images of single souls.